Our capacity to reason, intellectually and emotionally, is our human superpower. If we cannot find effective ways to engage with the complexity of our current reality, the increasing volatility and uncertainty will crush us, body and soul. Mindful approaches to complexity offer a practical solution for action, not a magical retreat.

What is VUCA?

VUCA is an acronym you have probably run across in your leadership training. Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, Ambiguity — it defined our lives during and since the pandemic, but it was always part of the human experience. The speed of change has increased, and volatility is more intense and perhaps even more broadly consequential than a century ago. And as our systems get more complex, they get more fragile. IF you want a quick primer on VUCA, check out Jonathan Woodson’s excellent explanation.

OODA and Orientate

So, this basic experience of the world as a volatile, complex, ambiguous, and uncertain place is not a new one. You may not, however, have heard of OODA (Observe, Orientate, Decide, Act), a decision loop developed by USAF Col. John Boyd that has been adopted by leaders in some industries to help mitigate the VUCA-ness of life and work. Discussions of OODA I’ve seen don’t always dig into the core of Boyd’s model, Orientate, in which he outlined five dimensions at play, nor do they always underscore how many internal feedback-loops he outlined. The basic idea, that we should seek information, consider it, and then decide to act seems to satisfy people. But when you try to apply this model, you’ll quickly realize how important Orientate is.

The basic sequence is the core of Inner Citadel Consulting’s system: Notice, Engage, Empower. What is brilliant about Boyd’s method as a response to difficult and complex situations is how much the decision process slows in the middle. Orientate is not just one thing — it is a full and detailed consideration of many factors that influence a single moment. Orientate suspends the moment so that we can turn it and look at it from all sides. It makes total sense to me, from my background in tai chi as a martial art and my mindfulness practice, to counter volatility with deceleration. It is also intelligent, cognitively and emotionally. And it reflects the basic concepts embedded in Stoic psychology of perception and decision-making.

OODA and Stoicism for Leaders

So, VUCA describes a situation, an evolving circumstance, in which the complexity of decision-making is made even more difficult to manage. OODA describes a solution to complex decision-making, of which the most significant part falls into Orientate. What I’ll lay out below is a way to enhance Orientate, the most difficult aspect of the model.

The thing I find most limiting about OODA is the relative lack of attention to the emotional response to VUCA. Cultural traditions, genetic heritage, previous experience, new knowledge, analysis & synthesis — very rational considerations. But not fully human without consideration of emotional experience and values. What I mean here is not that we need to integrate the expression of emotions, but we need to figure out the way in which the emotional response is not accounted for in the OODA loop. OODA privileges intellectual reason but does not fully account for emotional reason or value the role of emotions. Modern brain science by researchers like Lisa Feldman Barrett and David Eagleman demonstrate very clearly that the boundary between reason and emotion is a fantasy. Our brain does not have separate areas for different kinds of activity – it is an incredible matrix where experience of the world is managed in astoundingly complex ways.

I suggested that ambiguous, volatile, and uncertain complex moments are not new to the human being. Thinking about a solution for such moments is not new either. The Stoics framed a psychology of decision-making that, like the OODA loop, encourages us to decelerate and evaluate. Now, their particular solution to complex decision-making is tied up in a number of basic philosophical assumptions, such as strict materialism and a kind of cosmic optimism and providential worldview. This is all very interesting stuff and can get very distracting, but the upshot for this discussion is that the Stoic solution to complex decisions is ethical first and foremost – it places all ownership and responsibility for a decision and an action on the decision-maker. This ethical decision-making involves the whole human being in the decision. Stoic decision-making understands the central role of emotion and is eyes-wide-open about the pitfalls of emotion. Believe it or not, though, Stoicism is not about emotional suppression, but about emotional value.

Values and Decisions

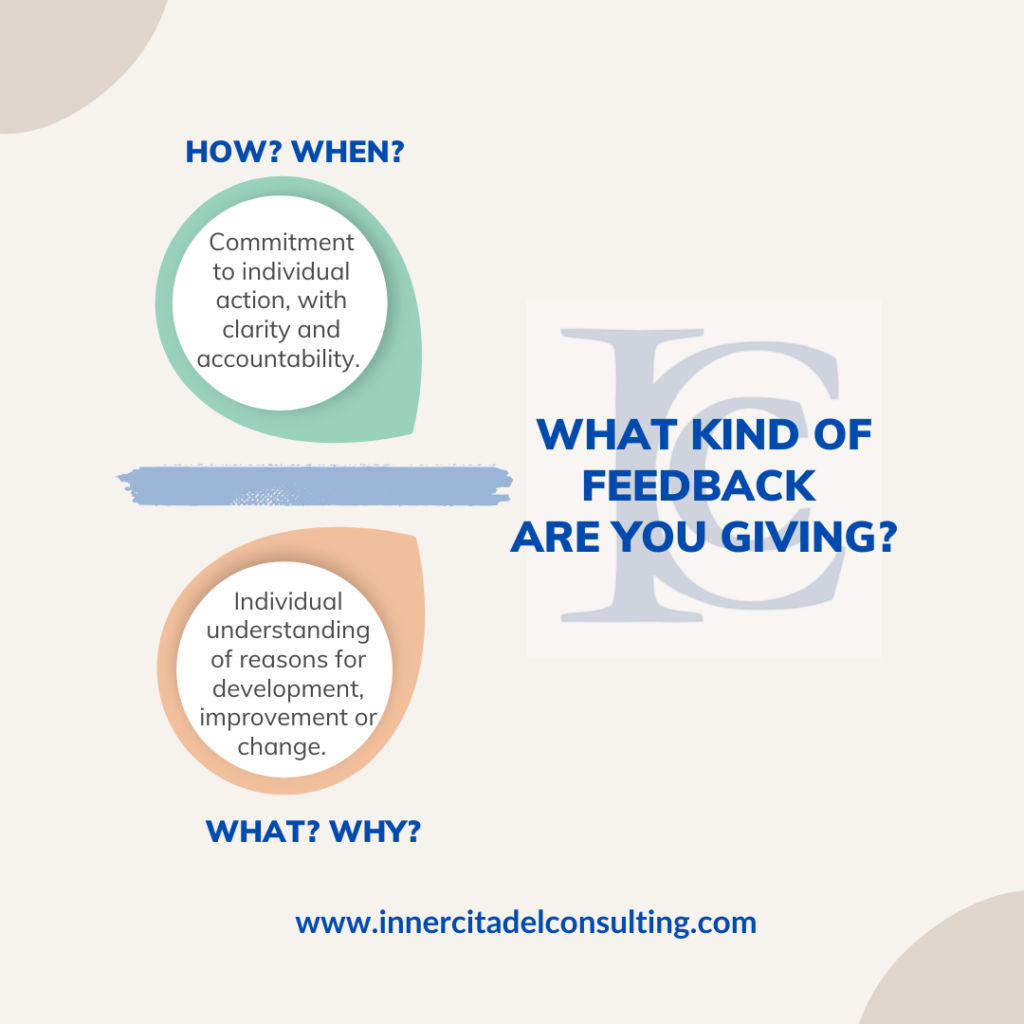

For the Stoics, human beings receive input not just from our senses but also from our thoughts and feelings (which are a kind of input). All of these sensory inputs form “impressions”, which are then “perceived” by our minds. The difference between the sensory input and a perception is very important, because while an object or event might produce the same basic impression for a number of people, we might each perceive something very different. When we perceive these impressions, especially of certain kinds of things (unfortunately, often the exact things that are surrounded in complexity), we eventually make evaluative judgements (this is good, this is bad, this hurts, this feels good). We could verbalize these perceptions and judgements, although we often process them far too quickly to even notice what’s going on much less put it into words. “There is a donut on the plate,” and suddenly the donut is in my hand and I’m eating — this is a series of impressions, perceptions, evaluative judgements, and (in the end) actions. At a minimum, I would have to have evaluated the donut as something I can eat. When we perceive and perform these evaluative judgments (what we might call intellectual and emotional judgments), according to the Stoics, we also can agree or not with the evaluation. They call this assent.

Stoic Assent and Orientate

Assent is the moment when, in this Stoic model, we can decelerate, slow down, examine the complexity. Without this capacity to decelerate — where we engage our full, human reasoning ability through our intellect and our emotions, we are simply animalistic, living only, I suppose, by instinct. For example, I see or smell or touch or think about the donut; I perceive it as a donut (as opposed to a bagel, or some other circular object); consciously or not I evaluate the “donut-event”, let’s call it; and then I act. I don’t just start eating it when I perceive it, like a dog chasing a squirrel. I must “assent” to any number of evaluative judgments. For example, that donuts are good for eating, that I like donuts of certain kinds, that this is a donut of one of the kinds I like, (maybe) that it’s a good thing to eat when hungry, or that a donut would be a good thing to eat right now, or that donuts make me happy and I feel sad right now … and so on, all the way to me licking my sticky fingers and wondering where the donut went. And this is the place where many of my decisions are revealed as ethical. “Was that the right thing to do?” “Was that even my donut to eat?” It’s also the place where I can make really terrible mistakes, and where we all act out of unconscious bias. Assent helps us see the ethical dimension of a decision before we act on it.

Assent for the Stoics created a belief, and the belief always precipitated an impulse to act. In simple terms, when I assented at every stage in the example above, I affirmed my belief, and that belief led to another perception and another evaluation, assent, belief… all the way to the final act of eating and the consequence. Now I have created experience that shapes the next event. At any point in the chain of perceptions and evaluations we have the capacity not only to verify the perception factually as much as possible but also to verify the evaluations emotionally, through emotional reasoning. Not only, “Am I hungry? Do I need these kinds of calories?”, but also, “What am I feeling when I see the donut? Do I really want the donut or something else? How will Sam feel about me eating the last donut?” The Stoics assert that when we assent to our evaluation, we affirm our belief in the evaluation, and an impulse to act arises. But they allow us to engage our humanity, to pause in assenting to an evaluation, sometimes even to withhold assent until we can properly decide, to spend more time evaluating — checking in with head and heart. “Why don’t I wait a few minutes to see if I still feel like eating the donut?” “I’ll ask Sam whose donut it is.” “I feel like I’m avoiding something by eating this donut — I wonder what else I could do.” Giving and withholding our assent is our human superpower. It involves our full capacity to reason, which is both intellectual and emotional. And when we combine our intellectual and emotional reasoning as leaders we can be decision-makers and leaders with humanity.

Leading with humanity

We are definitely living a VUCA-life these days, volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. We just can’t pause and reflect on every decision, although we can pause to reflect on many more than we do currently. And we need processes and models that help us cope, like Boyd’s OODA loop. But we also need models that will help us integrate the range of our reasoning capacities, to make fully human decisions. My donut example is kind of silly, but we can make it serious, deadly serious: I see a young African American man running on my street. I’m not including this to make light of the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, or any one of countless acts of racially motivated violence. I’m using this example because for the Stoics there is no real difference, from a psychological point of view, between the decision process that leads to eating a donut or murdering a human being. It is all ethical, it all rests on the capacity of a human being to evaluate their own perceptions, to orientate in the physical and mental world, and to regulate their own actions intellectually and emotionally, with full humanity and a willingness to withhold assent when they can’t be sure. Obviously, it’s more significant to us when we’re thinking about decisions at the level of equal human worth, but the ideal Stoic, the Stoic sage, makes every choice mindfully and ethically. It’s not that it’s impossible, it’s just that it’s really, really hard. We must be mindful in that full true sense – fully aware in the present moment without judgment.

Livin’ la vida VUCA

If we cannot find way to engage with the complexity of this coming year individually and collectively, the increase in all the aspects of VUCA we face will create chronic stress in our bodies and our workplaces. Systems like OODA work, of course. People wouldn’t use them if they didn’t. What I wonder is if they work fully enough to help us keep our humanity while the world is speeding up and growing more uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. Do you want to be more stoic and mindful about life? Then be more human, learn also to reason through what emotions you are feeling and what emotions are relevant to the decisions you make. Livin’ la vida VUCA seems inevitable these days, but let’s live it like human beings.

Peter spent a lot of time thinking about and teaching Stoicism at university and now integrates his experiences into emotional intelligence consulting and coaching. You can find his book on Seneca in your local bookstore or online.