I’ve recently shifted how I describe my work to, “I help leaders and teams have the conversations they really need to have but can’t manage on their own.” The ways I help vary according to the situation. Coaching, emotional intelligence training, organizational mindfulness, sense-maker training … these are all foundational skills for those conversations. But sometimes, when those skills are in place or when there’s some urgency, I need to help a leadership team do more than have a good conversation: make a decision. Some teams get stuck on talking and never get to making decisions.

How does your team make decisions?

If there’s a lot of difference around the table, convergent facilitation is often a good tool to help a team reach that decision together. So much of what happens in a team with unhealthy decision-making practices ends up looking (and feeling) like winners and losers in debate. But it doesn’t have to be that way, especially when we want the team to win, not the personalities around the table.

In my previous blogs I talked a bit about the different kinds of facilitation work I do. The first blog dove deep into multi-partial facilitation (or inter-group dialogue), the kind of dialogue that aims at finding common ground and establishing connection across difference. This kind of dialogue is great, of course, at bringing individuals from very different backgrounds together. But it is also an excellent approach for bringing members of a team together when there is conflict or when the stakes are high. We cannot truly move ahead together without understanding each other. But that doesn’t result in a decision, necessarily.

The second blog focused on the non-violent communication approach to dialogue. We use NVC to help people connect across conflict, not just to share understanding but to honor our essential human needs. NVC does not resolve conflict, it transforms it. As Marshall Rosenberg, the founder of NVC, said, “Every criticism, judgment, diagnosis, and expression of anger is the tragic expression of an unmet need.” By addressing unmet needs, the NVC space can be powerful and can go very deep. And as a way to deal with conflict at work it can be very successful, especially for conflicts that can’t be addressed in other ways. But it is also a lot of hard work for everyone. Again, NVC facilitation might result in a better way of working together by transforming conflict but it isn’t as effective at helping groups make decisions.

Facilitating Decision-Making

Facilitation for decision-making is different, because it extends that primary purpose of facilitation (understanding) more explicitly to decisions and actions. In my experience, when teams are consistently having trouble making decisions and moving to effective action, one of two things (or both!) are out of alignment.

An Example from Higher Education

First, people are coming into the decision-making process with very different perspectives and strategies. They are seeing the context only from their own specific perspective and are motivated for a result from their own needs. For example, we all agree we’re not hitting our markers for student enrollment to support our budget. The VP for Enrollment might want better marketing and communications to get the word out. The VP of Marketing and Communications might complain there isn’t a compelling story to tell about student success. The VP for Academics might suggest that students don’t get treated well when they visit campus. And so on. We can agree loosely on the problem (a budget shortfall), but not the solution.

The other misalignment is that people understand the context and data surrounding the decision in very different ways. So, the ways they perceive and express the problem are different. “We don’t have an enrollment problem at our college, we have too many highly paid faculty.” “It’s not that we don’t get enough people in the doors, the problem is that we can’t retain them.” “If faculty taught more, we could eliminate our adjunct budget.” “Our faculty aren’t paid enough because there is administrative bloat.” If someone else comes along and says that we just need to make campus look more attractive by planting some trees… This kind of misalignment can become toxic in a leadership team because we can’t even agree on the problem.

Convergent Facilitation

So the desired outcome of a decision-making facilitation is not just a decision, it’s a decision we all get behind. With convergent facilitation we create value by understanding how each of the team members sees the problem. When we can shape a common understanding of the problem, we can move to an effective (and lasting) solution. Because we have spent time with different perspectives and have agreed on a shared perspective, we are much more likely to have a high level of buy-in, even if the resulting decision is not a preferred strategy for some. And when there’s a high level of buy-in, the decision is less likely to be undermined when implemented.

The Three Phases

How does it work? For a fuller description of CF, check out Miki Kashtan’s pivotal book and her website. Most convergent facilitation consists of three explicit phases.

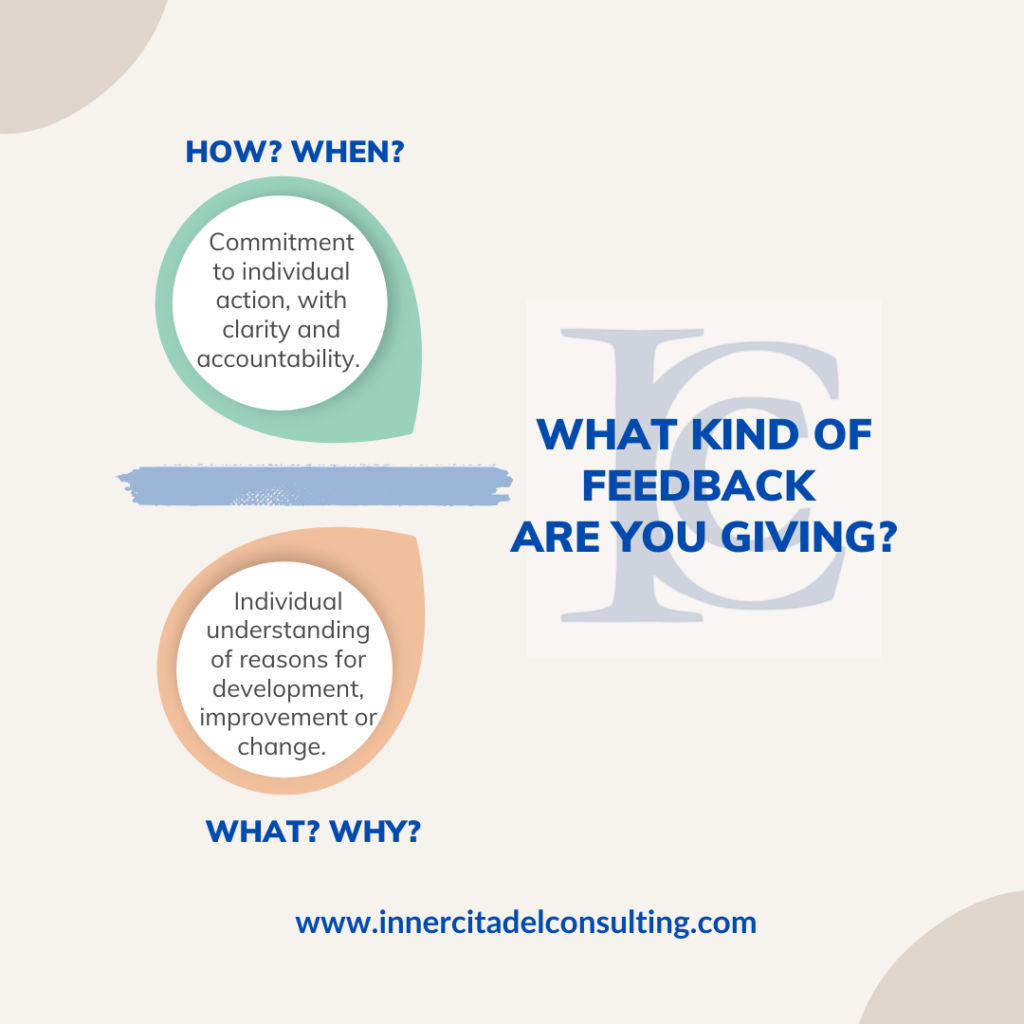

Non-Controversial Essence

The first is spent gathering people’s needs, their principles or values for action, and other kinds of considerations that affect their view of the problem and of potential solutions. What we are searching for as we gather and discuss these items are points of mutual need, as well as principles for action, and factors that affect decision-making, etc.

By getting these out in the open, we work to describe non-controversial essence (NCE), statements that are general enough to avoid specific strategies and deep enough to provide guidance. Any solution or decision needs to meet all NCEs the group can agree on. In our higher education example, an NCE in response to budget shortfall might be “integrity in our academic programs” or “a higher-than-average retention rate from 1st to 2nd year” or “a focus on experiential learning”.

Proposing Solutions

Once all these NCEs are expressed and agreed to by the whole group, we can move to phase two and start proposing solutions and actions. Here we lay out as many solutions as we can, assessing them against the NCEs, checking for objections and hard lines in the sand.

Willingness

In phase three, the group tackles the viable proposed actions/solutions begins the difficult work of surfacing disagreement, finding pathways to willingness (being willing to engage a solution), addressing and reconciling outliers, and ensuring that all needs expressed in earlier phases matter and are being honored. This is usually where specific concerns about implementation arise, but the groundwork has already been laid to work through concerns.

The Art and Science of Agreement

There is, obviously, an art and a science to guiding a group through this complexity. Even just the idea of “willingness” in a CF engagement is nuanced and negotiated by the stakeholders. Miki Kashtan’s incredible work and deep experience with this approach are the gold standard for success – successful CF facilitators are part guide and part enforcer. But the method is incredibly powerful with teams that have a history of poor collective decision-making because it turns the common process on its head. Instead of proposing actions first, which then get challenged and (often) attacked from different vantage points, get shouted down or shouted up, and get personal way too fast, CF asks us to establish values, stakes, and vantage points before trying to propose a solution. In my experience, this cuts through about 90% of the weeds people tend to wrap themselves in.

Want to make a powerful decision? Align on what matters first, then find a solution that everyone is willing to support. This is the kind of conversation that most teams can’t manage on their own. If you are wondering what conversations your teams are avoiding or which conversations they might be able to have more effectively, let’s connect!